…it is only in Beethoven’s settings that the rich musical potential of these Irish melodies is properly revealed… It takes a Beethoven to demonstrate what fine melodies they are… — Barry Cooper i

Why, therefore, did the folksong arrangements by a composer as eminent as Beethoven, not fare at least as well as Thomas Moore’s, and why are they so rarely performed today?

Some commentators attribute the neglect to the weakness, in terms of standard and appropriateness, of many of the texts that Thomson commissioned. It is important to remember that, although Beethoven was sometimes given information about the mood or tempo of each melody which he was sent, he did not know which texts were to be put to the airs. In fact, the texts were most likely not even written at that stage.

The standard of the texts was judged harshly by Alice Anderson Hufstader, who maintained that ‘most of the texts…must, in terms of posterity, be judged poor stuff indeed’ ii, describing the poetry as ‘an obedient supply of Hibernian absurdities’. iii

However, as early as 1927, in a letter to The Musical Times, the Irish historian and musicologist, William Henry Grattan Flood, pleaded:

In this Centenary Year of Beethoven it ought not to be an unprofitable commercial venture for some English publisher to risk a republication of Beethoven’s Irish Melodies, and, so far as possible, to substitute Moore’s lyrics for those sent by Thomson. iv

Almost 70 years later, while defending the poetry of William Smyth, Barry Cooper suggested that new texts could be substituted:

..it is not essential to use the texts Thomson chose… Beethoven designed most of his settings so that, as with hymn tunes, almost any texts with the right metre and character could be used, including, of course, texts in Irish. v

Portrait of Thomas Moore (1779 – 1852), Irish poet, singer and songwriter, by Martin Archer Shee (National Gallery of Ireland)

Tomás Ó Súilleabháin admired the Irish folksong settings immensely, and wanted to share his enthusiasm with fellow musicians and music lovers. His mission was to encourage performance of the songs, and he felt that the quality of many of the texts was a barrier to singers’ enjoyment of them.

He decided to choose alternative texts for most of the songs, by substituting poetry which he believed to be worthy of the melodies and of Beethoven’s accompaniments. Most of the poems are by Thomas Moore and Robert Burns, and Ó Súilleabháin felt that, if it had been possible at the time, Thomson may well have chosen such texts.

Beethoven provided duplicate settings for eight of the airs. (Thomson judged the piano parts of some of the first settings to be too difficult for local pianists!). Most of the first settings were not published until the latter half of the 20th century. There are also two airs to which no text had been appended. These settings are all texted and included in the present recording.

Another purpose of the publication and recording is to show that the settings were designed to work very well with just voice and piano. The string parts are optional and indeed some of the songs are more effective with just piano and voice(s). The mistaken idea that the strings are obligatory has possibly been another barrier to performance. In the recording, strings are included in about one third of the songs. The rest are performed with voice(s) and piano.

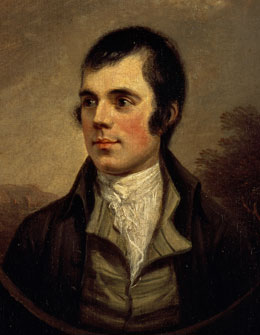

Portrait of Robert Burns (1759 – 1796), Scottish poet and lyricist, by Alexander Nasmyth (Scottish National Portrait Gallery)

Tomás Ó Súilleabháin greatly valued the enormous contribution of Barry Cooper to the scholarship and research of Beethoven’s folksong settings, and the publication and recording use the catalogue from Professor Cooper’s book, with his kind permission. vi

The performers of the DIT Conservatory of Music and Drama hope that the recordings will give much enjoyment to listeners, and that, with the revised texts, they will help the songs to achieve their deserved place in the repertoire of musicians.

Notes

In some melodies time values have been modified to suit the text. Where there are instances of redundant, ambiguous or impossible repeats in the manuscripts, the most logical and musical solution has been chosen. Occasionally a repetition of a bar or a phrase of a melody was missing, and this has been rectified. Sometimes a line of a poem has been repeated, to match the music.

These editorial decisions are fully explained in the notes to a new performers’ edition: Beethoven’s Irish Songs Revisited, to be published shortly after the release of this recording.

i Barry Cooper: Beethoven’s Folksong Settings as Sources of Irish Folk Music, Irish Musical Studies V, Dublin: Four Courts Press (1996), p. 80

ii Alice Anderson Hufstader: ‘Beethoven’s Irische Lieder: Sources and Problems’, Musical Quarterly XLV (1959), p. 359

iii Ibid., p. 360

iv The Musical Times, Vol. 68, No. 1009 (Mar. 1, 1927) p. 254

v Barry Cooper (as n. 1), p. 80-81

vi Cooper, Barry, Beethoven’s Folksong Settings: Chronology, Sources, Style (Oxford 1994)